In this article, I will focus on discussing the obligations that online platform providers have under the Digital Services Act (DSA).

Many services qualify under online platforms. These can be social media (e.g. Meta services such as Facebook or Instagram), a market place type service (e.g. Allegro, Amazon), or venues for publishing videos (e.g. Youtube). In recent years, the provision of services in the form of online platforms has become one of the leading sectors of the digital economy. Therefore, the EU legislator decided to pay a great deal of attention to these entities when creating the DSA and imposed a number of obligations on them.

Who is an online platform provider?

At the outset, it is important to identify who an internet platform provider is.

An online platform under the DSA is a hosted service (see our blog article [__] for more information on this) that stores and disseminates information to the public at the request of the recipient of the service.

However, the DSA provides exceptions to whether a particular service qualifies as an internet platform. Such an exemption applies where the activity is an insignificant or solely ancillary feature of another service or an insignificant function of the main service, and for objective and technical reasons cannot be used without such other service, and the inclusion of such feature or function in such other service is not a way to circumvent the application of the DSA.

Merely establishing that a particular provider meets the prerequisites of being an online platform does not at all mean that the DSA will need to be applied to it. If a provider is a micro or small enterprise as defined by the European Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC, then – with one reporting exception – it will not be required to implement the arrangements provided for online platform providers. These are as follows:

– micro enterprise – has fewer than 10 employees and a turnover or annual balance sheet total of less than EUR 2 million;

– small enterprise – has fewer than 50 employees and a turnover or annual balance sheet total of less than EUR 10 million.

But here, too, we have an exception to the exception 😊 Even if the online platform provider is a micro or small enterprise, it will have to comply with these obligations if, at the same time, it has the status of a very large online platform provider. This is because, with this qualification, the size of the provider and, above all, its outreach (more on this below) does not matter.

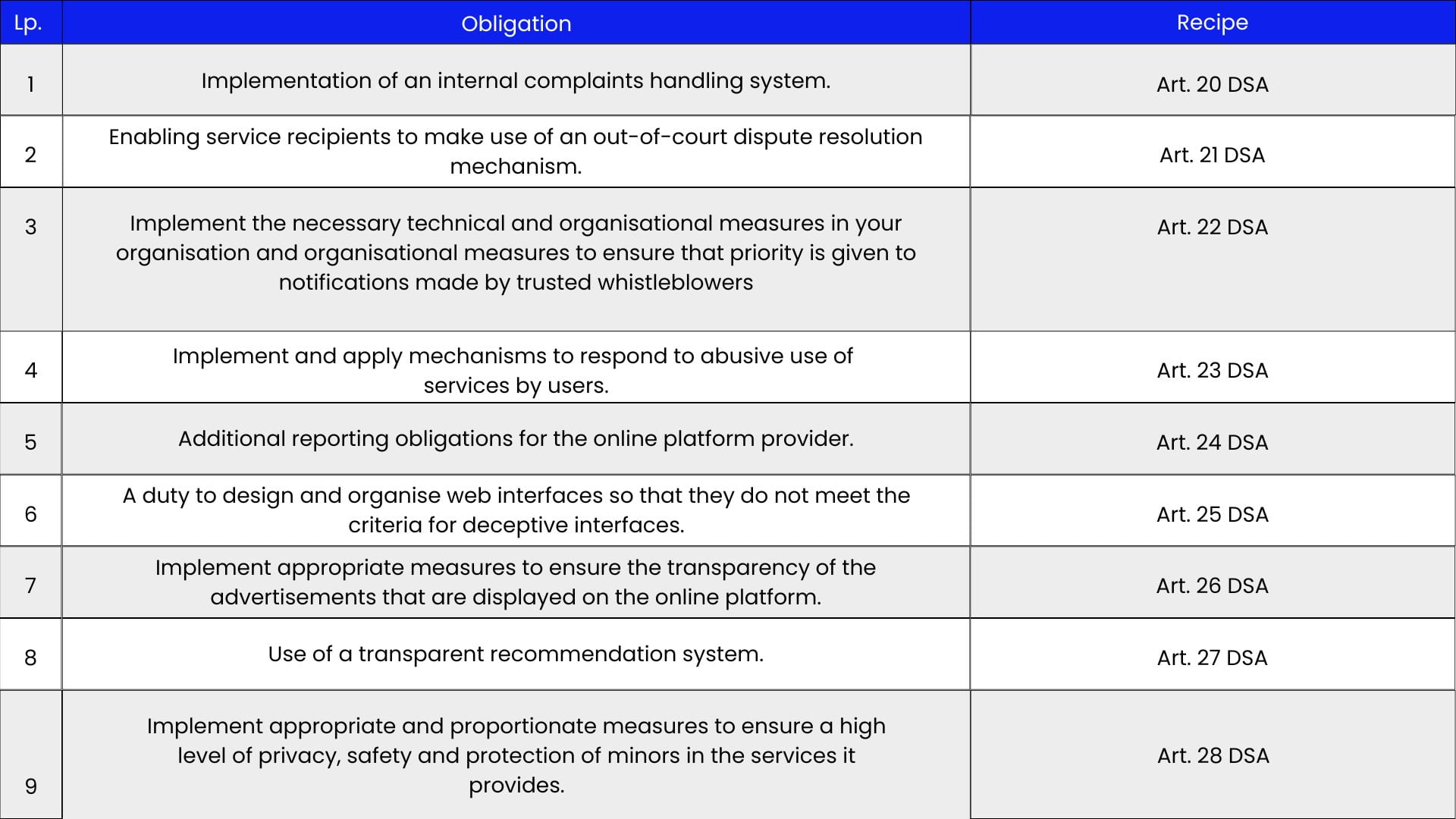

Below is a general summary of the obligations provided for DSA online platform providers only (Chapter III Section 3 DSA):

But beware: we still need to remember the following rules:

I. The online platform provider must also comply with the obligations that are provided for each intermediate service provider (Chapter III Section 1 DSA) and hosting service provider (Chapter III Section 2 DSA). This is because an online platform provider is, by definition, also a hosting provider, one of the types of intermediate services.

II. Further obligations for an online platform provider will arise if its platform allows consumers to conclude distance contracts with traders (so-called B2C platforms) (Chapter III Section 4 DSA).

III. Even more obligations will arise when the provider has the status of a very large online platform provider, i.e. it has an average number of monthly active service customers in the Union of at least 45 million and has been designated by the European Commission as a very large online platform.

IV. Last but not least, notwithstanding the obligations imposed by the DSA, an online platform provider must comply with the obligations imposed on it by other legislation (such as Regulation 2021/784 on the prevention of the dissemination of terrorist content on the internet, or the RODO).

The obligations of online platform providers that I have listed above are briefly summarised below.

Internal complaint handling system

This is an extension of the obligations imposed on each service provider relating to the moderation of content on its resources. Provider platform online must enable odbiorcom service, in that people who make the notification, by at least six months from the decision related to the moderation to the internal system of the complaint internal.

Po some time supplier platform issued a decision in which came to the position of the user A and removed with platform XYZ content user B, which was informed about it. User B does not agree with this decision and therefore files a complaint against it, which will be dealt with by that provider’s just internal complaint handling system.

Of course, this is one of the scenarios where the internal complaints handling system is applicable.

More information about this procedure can be found in this article.

Out-of-court dispute resolution mechanism

A further obligation on online platform providers is to ensure that users and eligible persons (i.e. filers who are not users) can use an out-of-court dispute resolution mechanism.

It is important to note that this is not another stage of the online platform provider’s handling of the case. The case is resolved by an external entity. The online platform provider must indicate to the interested party that the right to use this measure.

The interested party may refer the dispute resolution request to an out-of-court (e.g. certified) body. As a general rule, the online platform provider may not refuse to enter into such a case.

Prioritisation of requests

It is incumbent on the provider of the online platform to implement the necessary technical and organisational measures within its organisation to ensure the prioritisation of notifications made by trusted whistleblowers. These are entities identified by the Digital Services Coordinator that:

- have specific expertise and competences to detect, identify and report illegal content;

- are independent of online platform providers;

- take steps to report accurately and objectively and with due diligence.

Meeting such an obligation may involve, for example, establishing a separate reporting channel for these entities, independent of reports made by others.

Mechanisms for responding to abuse of services

The DSA requires the provider of an online platform to implement mechanisms that the provider can use when abusers use the services it provides. Very often, this is done by those engaged in ‘trolling’.

Firstly, the provider suspends for a reasonable period of time and after issuing a prior warning the provision of services to recipients of the service often transmitting obviously illegal content.

Secondly, the provider suspends for a reasonable period of time and after issuing a prior warning, the processing of reports made through the reporting and action mechanisms and complaints made through the internal complaint handling systems by persons or entities making frequently obviously unfounded reports or by complainants making frequently obviously unfounded complaints.

For example, user A, who has an account on the social networking platform XYZ, reports to its provider as potential illegal content any post by user B that concerns the political situation in the country. User A does not agree with the views of user B, as he himself advocates a different political option. On the other hand, without the need for expertise, the provider of the XYZ platform notices that none of user B’s contributions contain illegal content and that the contributions themselves are constructive criticism. In such a situation, the XYZ platform provider warns user A that he or she is abusing his or her reporting rights and calls on him or her to stop this practice. Despite the call, user A continues to make reports of user B’s statements. Consequently, the provider suspends the processing of user A’s submissions for 1 month.

Additional reporting obligations

An online platform provider has more reporting obligations than a standard intermediate service provider. Below are examples of these obligations.

In addition to the information contained in Article 15 of the DSA (see the article at this link for more information), the online platform provider must also make the following data publicly available (usually on the online platform’s website):

- related to the conduct of disputes by the online platform provider:

- the number of disputes submitted to out-of-court dispute resolution bodies;

- the results of the resolution of those disputes; and

- the median time taken to conduct dispute resolution proceedings; and

- the share of disputes in which the online platform provider has implemented the decisions of that body.

2. The number of service suspensions broken down by suspensions made due to:

- transmission of manifestly illegal content;

- making manifestly unfounded claims; and

- the filing of manifestly unfounded complaints.

In addition, at least every six months, providers shall, for each online platform or search engine, publish information on the average number of active monthly users of the service in the Union on a publicly accessible section of their online interface.

At the same time, providers of online platforms or search engines shall, upon request and without undue delay, provide information on the average number of monthly active recipients of the service in the Union to the digital services coordinator responsible for the place of establishment and to the European Commission.

Prohibition on the use of dark patterns

An online platform provider must not design, organise or operate its online interfaces in a way that misleads or manipulates the recipients of the service or otherwise materially interferes with or impairs the ability of the recipients of their service to make free and informed decisions. The DSA refers to these types of practices as ‘deceptive web interfaces’, but the business most commonly uses the phrase ‘dark patterns’. The use of dark patterns is an extremely common phenomenon, including in e-commerce. Through such interfaces, users often buy products they do not need at all, or buy more than necessary.

It should be noted here that the regulations of the RODO and the Unfair Market Practices Directive (implemented in the Polish legal order as the Act on Counteracting Unfair Market Practices) take precedence over the DSA provision in this respect.

Transparency of online advertising

Online platform providers that present advertisements on their online interfaces shall ensure that – with regard to each specific advertisement presented to each individual recipient – the recipients of the service are able to clearly, explicitly, concisely and unambiguously and in real time:

- state that the information is an advertisement;

- state, on behalf of a natural or legal person is presented advertisement;

- identify the natural or legal person who paid for the advertisement, if that person is not the natural or legal person referred to in point b;

- find relevant information, extracted directly and readily from the advertisement, on the main parameters used to determine the target audience to which the advertisement is presented and, if applicable, how those parameters are varied.

In addition, providers provide a function for service recipients to make a declaration as to whether the content they provide is or contains commercial information (do you sometimes see on platforms that a particular material is ‘sponsored’? 😊).

Another important obligation imposed on online platform providers is the prohibition to present profiling-based advertising to the recipients of the service under the provisions of the RODO using special categories of personal data (e.g. data on health status or political views).

Use of a transparent recommendation system

Online platform providers that use recommender systems shall set out in simple and accessible language in their terms of service the main parameters used in their recommender systems, as well as any options for service recipients to change or influence these parameters.

The main parameters explain why certain information is suggested to the service recipient. These include, at a minimum:

- the criteria that are most relevant in determining the information suggested to the service recipient; and

- the contribution of each parameter (‘how much they weigh’) in determining the recommendation to the user.

In other words, this way we should know that we often see pictures of funny cats on the platform because we watch a lot of videos with them in attendance 😊.

If several options are available for recommender systems that determine the relative order of the information presented to the recipients of the service, providers shall also provide a function that allows the recipient of the service to select and change the preferred option at any time. This function must be directly and easily accessible in the specific section of the web interface of the online platform where the information is prioritised.

Protection of minors on the internet

A final area of obligation for online platform providers relates to the use of their services by minors. These obligations are as follows:

- the introduction of appropriate and proportionate measures to ensure a high level of privacy, safety and protection of minors in the services provided by providers (the solutions developed in the RODO are very helpful here);

- prohibiting providers from presenting profiling-based advertising on their interface using the service recipient’s personal data if they know with reasonable certainty that the service recipient is a minor.

Compliance with the above obligations does not oblige online platform providers to process additional personal data in order to assess whether the service recipient is a minor.